Caipirinha - Medicine for the soul

Brazil's Pride: Watching Bossa Nova Bloom

For those of you waiting for a new cocktail to try.

Jayme Leão stands in the kitchen of his Avenida Atlântica apartment, carefully slicing limes into perfect wedges. Through the doorway, he can see his seventeen-year-old daughter Nara seated in the center of the living room, her guitar balanced delicately on her knee, a circle of entranced musicians surrounding her. The sea breeze gently billows the curtains, carrying salt air and the distant rhythm of waves crashing against Copacabana Beach seven stories below.

He smiles to himself as he presses the wooden muddler against the lime wedges and sugar in the bottom of a glass, releasing both juice and aromatic oils from the peels. The familiar ritual of preparing caipirinhas calms him, giving his hands something to do while his heart swells with a father’s quiet pride.

“More sugar in mine, please, Seu Jayme,” calls Ronaldo Bôscoli from the living room, flashing a charming smile that doesn’t quite overcome Jayme’s paternal suspicion. The young lyricist has been paying particular attention to Nara lately, and while Jayme appreciates his talent, he’s not entirely convinced of his intentions.

“Of course,” Jayme responds graciously, adding an extra spoonful of sugar to one of the glasses. As a lawyer, he understands the value of diplomacy, especially when hosting gatherings that have grown increasingly significant in Rio’s musical landscape.

When Nara had first asked permission to invite her guitar teacher, Roberto Menescal, over to practice, Jayme and his wife had readily agreed. When those sessions expanded to include Menescal’s friends, they adapted. Now, hardly a week passes without their living room filling with musicians, composers, and poets on the cusp of recognition. All drawn to his daughter’s unpretentious warmth and genuine passion for this new music taking shape.

Jayme pours cachaça over the muddled limes, the clear liquid catching the amber light from the kitchen lamp. He’s developed his own refinements to the traditional recipe over the years—a touch less sugar than most use, slightly more lime, and always the best cachaça he can find, not the harsh industrial varieties. He’s learned each guest’s preference: João Gilberto prefers his strong with minimal sugar; Vinícius de Moraes enjoys his sweeter; Tom Jobim likes extra lime.

In the living room, Nara begins playing a delicate bossa nova pattern, her fingers moving with growing confidence across the strings. Her playing lacks the technical brilliance of João Gilberto, who sits nearby watching with approval, but possesses a pure, unaffected quality that brings out the emotional essence of the music.

“That’s it, Nara,” encourages Carlos Lyra. “Just like that. Now try it with the melody.”

She begins to sing “Insensatez” in her characteristic voice—soft, almost whispered, with perfect intonation. Antônio Carlos Jobim, who composed the piece, nods appreciatively from his position near the window, a cigarette balanced between his fingers.

Jayme pauses his preparations, momentarily transfixed. When had his little girl transformed into this poised young woman at the center of Rio’s most exciting musical movement? He remembers her at seven, struggling with her first guitar, her small fingers determinedly pressing against the strings until they left indentations on her fingertips. He remembers her tears of frustration and her refusal to quit, practicing until her hands ached.

He adds ice to the glasses, the cubes cracking slightly as they meet the room-temperature mixture. The sound brings him back to the present, to this apartment filled with the future of Brazilian music.

Balancing five caipirinhas on a tray, Jayme moves into the living room, distributing them among the guests with the easy hospitality that has made the Leão apartment a favorite gathering place. As he hands João Gilberto his drink, the guitarist meets his eyes.

“Your daughter has something special, Seu Jayme,” João says quietly, his normally reserved manner giving the words particular weight. “Her ear, her feeling for the music, you cannot teach these things.”

“Thank you,” Jayme responds, emotion making his voice slightly gruff. “We always knew she was musical, but this...” he gestures to the gathered musicians, many of whom are far older and more established than Nara, “this we could not have imagined.”

He settles into his favorite chair, slightly removed from the circle but with a perfect view of his daughter. His presence is unobtrusive but essential. The responsible adult who makes these late-night sessions possible. He ensures there’s always enough food and drink, and maintains the respectful atmosphere that allows creativity to flourish.

Nara looks up from her guitar, catching his eye across the room. She smiles, somehow both shy and radiant, and he raises his glass in a small toast.

Vinícius de Moraes, the poet whose lyrics have given such depth to this emerging music, leans toward Jayme conspiratorially. “You know,” he says, his voice carrying the warmth of the caipirinha he’s already half-finished, “they’ll remember these nights. Someday, these gatherings in your living room will be part of Brazilian musical history.”

Jayme sips his drink, the familiar taste of lime, sugar, and cachaça momentarily distracting him from the weight of Vinícius’s words. Could that be true? He watches as João Gilberto takes the guitar from Nara, demonstrating a particular chord progression. His daughter’s face is intent, absorbing every nuance. Around them, the other musicians lean forward, equally attentive. Something extraordinary is happening here. He can feel it.

As the night deepens, Jayme makes another round of caipirinhas. The conversations have grown more animated, the music more exploratory. Tom Jobim is at the center now, describing a new composition inspired by the very beach visible from their windows. Baden Powell has arrived, bringing a different energy with his more percussive playing style. Through it all, Nara’s natural musicality and genuine enthusiasm make her essential despite her youth.

Near dawn, when most of the guests have left and only João Gilberto remains, still quietly playing variations on a theme, Jayme finds Nara in the kitchen, washing glasses.

“You should sleep, filha,” he says gently. “It’s very late.”

She turns to him, her eyes bright despite the hour. “Did you hear what João said about the new song? And Tom wants to include me in the recording session next week.”

Jayme nods, helping her dry the last of the glasses. “I heard. I’m proud of you, Nara. Not just for the music, but for creating this...” he searches for the right word, “this community.”

She leans against him briefly, her head resting on his shoulder in a gesture that reminds him of her childhood. “I couldn’t do it without you and Mamãe. The way you welcome everyone, the way you make space for us.”

From the living room comes the gentle sound of João’s guitar, exploring the boundary between chord and melody in that distinctive way that has influenced all of them. The first light of dawn is beginning to illuminate the Atlantic, visible through the windows of their Copacabana apartment.

Jayme puts his arm around his daughter’s shoulders. “The music happens because of you, Nara. We just provide the caipirinhas.” They share a smile, both knowing it’s both more and less complicated than that. It is a father supporting his daughter’s passion, unwittingly helping to birth a musical revolution that will someday be known worldwide as Bossa Nova.

As they stand together in the kitchen, the familiar scent of lime still in the air, João begins playing the opening notes of “Chega de Saudade.” The music seems to crystallize something essential about Brazil itself, sophisticated yet accessible, melancholy yet hopeful, traditional yet utterly new. And at the heart of it all is Nara, her quiet determination having created a space where this transformation could occur.

Jayme refills João’s glass one last time, then returns to sit beside his daughter as the music fills their home, knowing with a father’s intuition that they are witnesses to something that will outlive all of them, a new sound being born note by note, night by night, in the living room of their Copacabana apartment.

Double click below and then press play to listen to Nara’s music.

The Caipirinha, Brazil’s national cocktail, emerged from humble medicinal origins to become a global symbol of Brazilian culture and hospitality. This deceptively simple combination of cachaça, lime, and sugar tells a story of colonial trade, agricultural innovation, and the vibrant spirit of South America’s largest nation.

The story begins with cachaça, Brazil’s indigenous spirit, first distilled in the 16th century during the Portuguese colonial period. Sugar cane plantation workers discovered that the foam produced during sugar production could be fermented and distilled, creating a potent spirit initially known as “pinga” or “aguardente da terra” (fire water of the land). Unlike rum, which is typically made from molasses, cachaça is distilled directly from fresh sugar cane juice, giving it a distinctive grassy, botanical character.

The Caipirinha’s origins are rooted in folk medicine. In the early 1900s, in the state of São Paulo, a popular cold and flu remedy combined cachaça with lime, honey, and garlic. As the story goes, people gradually dropped the garlic and replaced honey with sugar, creating a more palatable drink that would eventually become the Caipirinha. The name itself comes from “caipira,” meaning someone from the countryside, with “inha” being a diminutive suffix -- literally meaning “little countryside drink.”

During the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic, the mixture gained popularity as a supposed remedy, prescribed by doctors and embraced by the population. Whether or not it had any medical merit, the combination stuck, and the Caipirinha began its journey from medicine to mixer.

The drink remained largely a local phenomenon until the 1930s, when President Getúlio Vargas began promoting Brazilian culture as part of his nationalist agenda. Cachaça and the Caipirinha became symbols of Brazilian identity, representing the country’s unique fusion of indigenous, African, and European influences.

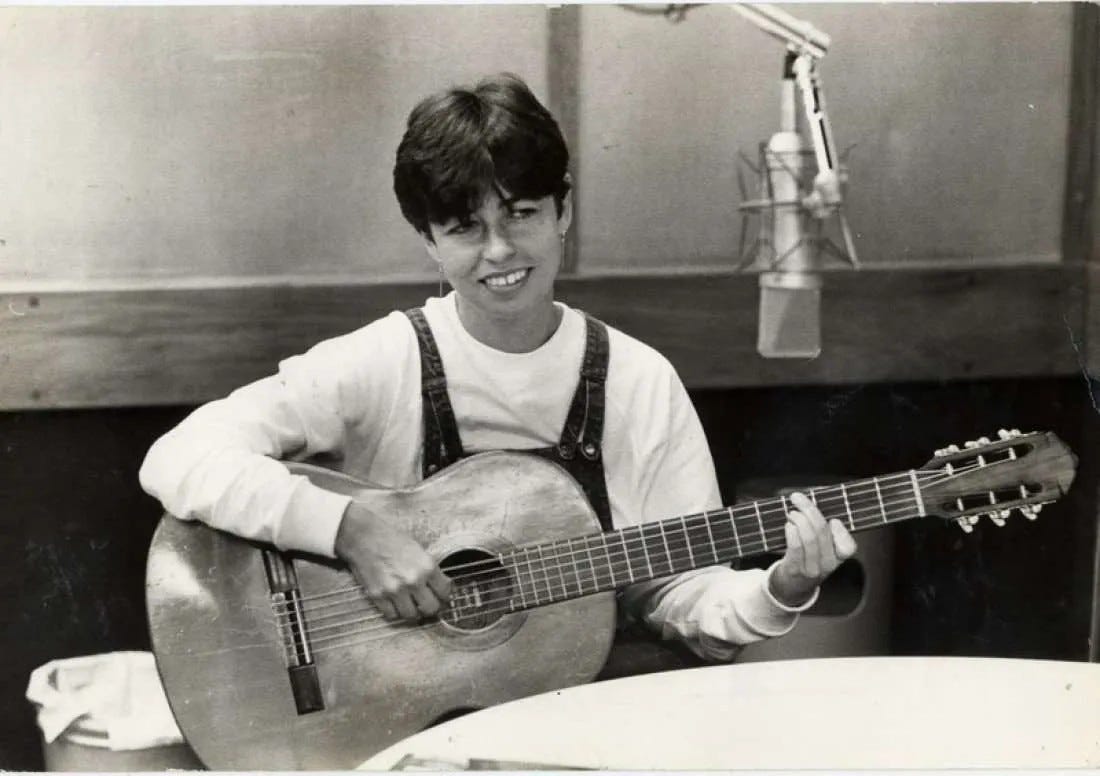

The cocktail’s international journey began in earnest during the Bossa Nova explosion of the 1950s and ‘60s. As the relaxed, sophisticated sounds of Bossa Nova captivated global audiences, the Caipirinha became a natural companion to this distinctly Brazilian musical movement. In the apartment of Nara Leão, often called the “Muse of Bossa Nova,” the intimate gatherings that birthed this revolutionary music style frequently featured Caipirinhas being passed among musicians like João Gilberto, Antonio Carlos Jobim, and Vinícius de Moraes. Leão’s Copacabana apartment, with its view of the beach, became the epicenter where Brazil’s cultural renaissance took form - with both Bossa Nova melodies and the refreshing lime-and-cachaça cocktail embodying the laid-back sophistication that characterized Brazil’s post-war cultural emergence. As international musicians and tourists flocked to Rio to experience Bossa Nova firsthand, they invariably encountered the Caipirinha, carrying its reputation back to their home countries and cementing its status as Brazil’s signature drink.

In 2003, Brazil made the Caipirinha’s status official by declaring it the country’s national cocktail. This wasn’t just cultural recognition, it was economic strategy. Brazil began actively promoting cachaça exports, leading to the spirit’s recognition as a distinctive Brazilian product by the United States in 2012. This agreement meant that only sugarcane spirits produced in Brazil could be labeled as cachaça in the U.S. market.

Today, the Caipirinha has inspired countless variations. The Caipiroska (made with vodka) and Caipiríssima (made with rum) have become popular alternatives, while fruit variations like passion fruit, strawberry, and mango have expanded the drink’s appeal. In São Paulo’s sophisticated cocktail scene, mixologists experiment with premium cachaças and innovative techniques while respecting the drink’s rustic origins.

The Caipirinha embodies the Brazilian concept of “jeitinho” -- finding a creative way to make things work. What began as a home remedy transformed into a celebrated cocktail that captures Brazil’s inventive spirit and zest for life. Whether enjoyed on Copacabana beach or in a high-end cocktail bar, each sip of a Caipirinha delivers a taste of Brazilian history, culture, and joie de vivre.

The classic recipe remains straightforward:

2 oz cachaça

1 lime, cut into wedges

2 teaspoons sugar

Ice cubes

The technique, however, is crucial. The lime wedges and sugar are muddled together to release both juice and essential oils from the lime peel, creating a complex citrus profile that simple juice alone cannot match. The mixture is then combined with cachaça and ice cubes (cubed ice is better as it delays the melt), creating a drink that’s simultaneously sweet, sour, and strong.

What an interesting story! Michael, you write beautifully, adding just the right amount of detail to make us feel like we were there. Can’t wait for your next post.

Lastromom