Marking Territory - The Architect's Transgression

E.1027: A House of Discord

The Mediterranean sun blazed through E.1027's windows, casting elongated rectangles of light across the pristine white walls. Le Corbusier stood naked before them, his body weathered and tanned like the rocks below the villa, paintbrush suspended in his hand.

His right leg bore a jagged scar looking like a giant shark bite. He had been run over by a motorboat just a few months before. The propeller had run down his leg and not across; if it had crossed his leg he would have lost it. The summer was hot and it had been hard to stay out of the water as he healed.

The year was 1939, and Europe teetered on the brink of war, but here, in this modernist masterpiece clinging to the cliffs of Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, he waged his own private battle against its absent creator.

E.1027 was the name given to this house by its creators Eileen Gray and Jean Badovici, and the name intertwines their initials: the E is for Eileen, the 10 and the 2 for the tenth and second letters of the alphabet, J and B, and the 7 is for G.

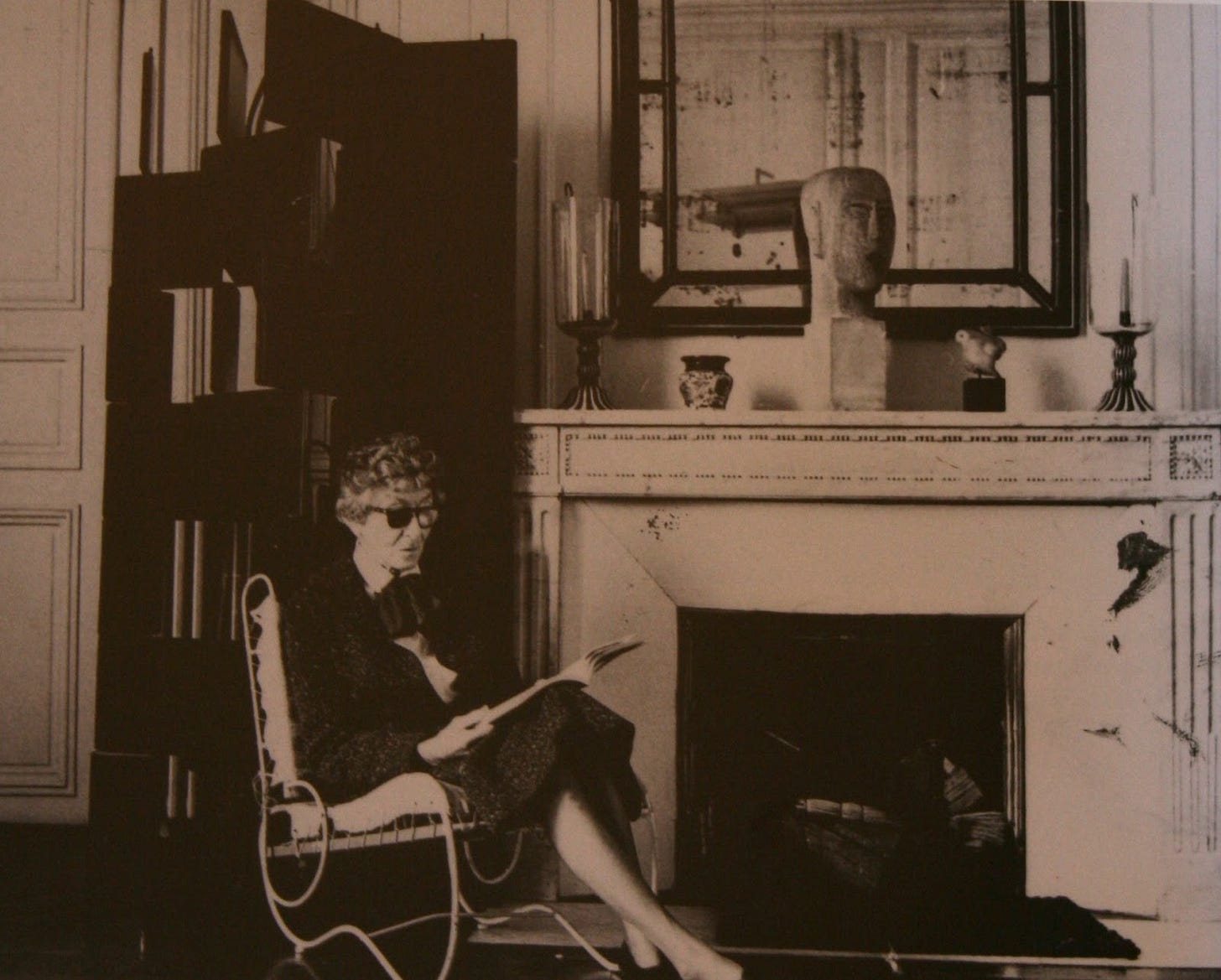

Eileen was Irish and had moved to Paris after falling in love with it during a visit for the Paris Exposition in 1900.During the first world war she had been an ambulance driver, surrounded by an amazing collection of women some of whom would go on to be her lovers and friends.

In 1922 she opened her own gallery selling furniture that she designed. It was called Jean Desert (a man's name) as it was not considered respectable for a woman to be in this business.

Her lover Jean was a Hungarian architect who had been the driving force behind the publishing of L'Architecture Vivante magazine, a digest of avant-garde architecture from around Europe. He encouraged Eileen to design a house for him which became E.1027.

Eileen designed and had this house built between 1926 and 1929, living full time in primitive conditions while the house was built. In 1929, Eileen and E.1027 were featured in L'Architecture Vivante. She had great optimism for the villa; Gray designed it with input from her then lover Jean Badovici as a peaceful refuge for them both.

"One must build for the human being, that he might rediscover in the architectural construction the joys of self-fulfillment in a whole that extends and completes him, even the furnishings should lose their individuality by blending in with the architectural ensemble."

She and Jean lived together here for the next few years. Eventually in 1932, Eileen and Jean split up, and Eileen left and built a new house for herself in a nearby town. She remained on good terms with Jean and would visit occasionally but not often.

Jean was good friends with the most influential architects of the day including Le Corbusier. In fact, Le Corbusier was a good friend of Badovici's and was obsessed with E.1027. After Gray and Badovici split in 1932, Badovici inherited the house and invited Le Corbusier and his wife.

The villa is essentially a modernist rectangle perched upon the Cap-Martin cliff face. It adopts some aspects of Le Corbusier's five points of new architecture (concrete piles, open plan rooms, a roof garden, horizontal windows and a "free" facade) which the Swiss-French architect had published in his seminal 1923 book *Vers Une Architecture*.

However, despite Corbusier's call for openness within and without, privacy is a main objective of E.1027. On the exterior, floor-to-ceiling concertina windows open to the Mediterranean Sea, providing light and views, yet rolling shutters and two strips of canvas shield the villa's interiors from being seen, thereby also blocking harsh afternoon sunlight and framing the seaside vista.

Le Corbusier was born in Switzerland, he adopted his pseudonym in the 1920s and revolutionized architecture through his philosophy of the house as a "machine for living." He had designed several iconic buildings including Villa Savoye and the Swiss Pavilion, published influential works like "Vers une Architecture," and established the five points of modern architecture. His work championed functionalism, concrete construction, and open floor plans.

During the 1930s he had spent time in Algiers where he had been painting, nudes and women. This was his relief from the stresses of his life.

This was Le Corbusier's second stay at E.1027 down in the Riviera; he came at the invitation of his friend Jean who owned the house. Gray, though never trained as an architect, had created a place of beauty and perfect function. She had taken Le Corbusier's own ideas and added the touch of the divine, the empathy that he recognized he lacked.

On his first visit, that empathy had so inflamed him he had felt the need to defile her work, to claim it, to make his mark upon the divine. He had painted in a fury two murals using paints provided by Badovici. Explicit works of masculine dominance, they spoke to his insecurity and shame.

This time he had different hopes for his murals. He had stayed up late talking and drinking wine with Jean as they had always done. Le Corbusier had undressed to ensure the maximum of ritual and symbolism could be read into his work, his nakedness freeing him from not only his clothes but from society's expectations. He could proceed to defile, to appropriate, to vandalize without the limitations of what society thought decent.

The smell of fresh paint mingled with the salt air that drifted up from the sea. His muscles ached from hours of work, but he couldn't stop—wouldn't stop—until the image in his mind found its way onto Eileen Gray's wall. The curves of the three women emerged beneath his brush: bold, primitive, almost violent in their sexuality. One figure, he imagined as Gray herself, proud and distant. The second, Jean Badovici, the man who had given him indecent access to this gem. And the third... perhaps himself, though he would never admit it openly, a figure both observer and intruder in this space that had never truly been his.

Sweat trickled down his spine as he worked, the afternoon heat intensifying. The sound of waves crashing against the rocks below provided a rhythm to his brushstrokes, like a primitive drum beating in time with his artistic frenzy. He stepped back, eyes narrowing as he assessed his work. The mural was an invasion, he knew that. Each stroke of paint was a claim staked, a signature scrawled across another artist's canvas. But he couldn't help himself—the blank walls had called to him like virgin snow begging for footprints.

"Magnifique," he muttered, running a hand through his hair, leaving a streak of paint across his temple. The women on the wall stared back at him, their simplified forms somehow more real than any naturalistic representation could be. They were primitive, raw, almost savage in their execution—everything that Gray's precise, refined design was not. Where she had created harmony, he introduced discord. Where she had employed subtlety, he answered with bold declaration.

The light shifted, and for a moment, the shadows of the window frames fell across his mural like prison bars. He thought of Gray, imagining her reaction when she would eventually see what he had done to her masterpiece. Would she understand? That this wasn't mere vandalism, but a dialogue between artists? That her pristine white walls had been too perfect, too controlled, too feminine?

Le Corbusier dipped his brush again, adding another bold stroke. The paint dripped slightly, a crimson tear running down the wall. He left it, seeing in that imperfection a truth about what he was doing here. This was no mere decoration—it was a claiming, a marking of territory, as ancient as cave paintings and equally primal. He worked naked not just for convenience, but as a kind of ritual, connecting him to something more primitive than Gray's sophisticated modernism.

The sea breeze carried the faint sound of distant voices—locals, perhaps, or visitors making their way along the coastal path below. He ignored them, lost in his creative fury. The three women took on a life of their own, their forms seeming to dance across the wall, mocking the careful geometry of Gray's architecture. Each brushstroke was an act of both creation and destruction, beauty and violation intertwined.

As the sun began to set, casting the room in amber light, Le Corbusier finally stepped back, exhausted but satisfied. The mural was complete—a permanent mark on Gray's pristine canvas, as indelible as his influence on modern architecture itself. He knew, even then, that this act would be seen as a transgression, perhaps even a violation. But art, he told himself, had always required such boldness, such willingness to break boundaries and challenge conventions.

He cleaned his brushes methodically, the water in his jar turning murky with paint, while the three women watched from the wall, their simplified forms holding secrets that would perplex and provoke viewers for generations to come. As darkness fell over E.1027, Le Corbusier dressed slowly, his body tired but his mind alive with the energy of creation—or destruction. He had left his mark, for better or worse, on Gray's masterpiece. History would judge whether it was an act of artistic dialogue or architectural vandalism.

When the war broke out, Le Corbusier worked with the Vichy government while German soldiers used E.1027's walls for target practice. After the war, he tried to buy the house but failed, purchasing property nearby where he built a small cabin completed in 1951, the "Cabanon de vacances" overlooking Eileen Gray's creation. It was a prefabricated building; the panels were built in Corsica and delivered by ship and train and assembled on site.

He spent August in this minimalist home here every year. The cabin did not have a kitchen but was attached to a fish restaurant owned by a good friend of Le Corbusier. He ate there every night. He worked in a small builder's cabin in front of the Cabanon. He swam every day in the sea in front of E.1027 and he observed its decline. On August 27, 1965, against his doctor's orders, he went swimming; that morning Le Corbusier's body washed up on the shores below.

Gray lived to be 98, dying in her Paris apartment in 1976, surrounded by her own furniture designs. E.1027's subsequent history proved equally dramatic: its owner Marie-Louise Schelbert died mysteriously in 1980, after her physician Peter Kägi had secretly sold off Gray's furniture. Kägi inherited the house, hosting drug-fueled orgies until his murder in the living room in 1996.

Today, restored and open to the public, E.1027 stands as a testament to architectural genius and human complexity, its walls still bearing Le Corbusier's provocative marks.