The Moscow mule - A shot at something new

Copper and Steel

The February wind howled through Pittsburgh's Strip District, carrying the acrid smell of sulfur from the steel mills and the promise of more snow. The Allegheny River had frozen solid enough that men were ice fishing between the barges, their dark silhouettes visible from the windows of Kelley's Bar & Grill. The neon clock above the bar read 10:30 AM when John Martin stepped in, brushing coal dust from his Brooks Brothers suit. Even two years after trading his colonel's eagles for civilian clothes, he carried himself with military precision - his oxford shoes polished to a mirror shine, despite Pittsburgh's notorious slush.

Marie Kowalski looked up from arranging shot glasses, her steel-gray hair pulled back in a practical bun. The morning regulars were already filing in - mill workers from the night shift at Jones & Laughlin, their faces still smudged with soot, mixing with former servicemen who couldn't shake the habit of early rising. A torn "We Can Do It!" poster clung stubbornly to one wall, its corners curled with age. Marie had one just like it at home, carefully preserved alongside the telegram about Danny's death at Normandy. His landing craft had barely made it to the beach.

"Looking awful fancy for the Strip," Marie called out as Martin arranged his display with methodical precision - copper mug, Smirnoff, Cock 'n' Bull ginger beer. Each item lined up with the same care she'd once seen military men clean their rifles.

"The hazards of doing business in the Steel City," Martin replied, adjusting his signet ring - a small reminder of Cambridge days, before the war had changed everything. He withdrew the Polaroid Model 95 from its case with reverence, its chrome and black bellows drawing immediate attention in the bar's dim light.

Marie felt her professional detachment crack like spring ice on the river. The camera transported her back to the Westinghouse plant in East Pittsburgh, where similar models had documented their assembly lines for the Navy - part of the endless drive for efficiency that had defined the war years. "That one of them instant picture machines?" she asked, moving closer. "Like the ones they used for reconnaissance?"

Martin nodded, pleased by her technical knowledge. "Latest model. Polaroid's changing everything - no more waiting days for development. Take a picture, wait a minute, there it is."

"Like magic," Marie murmured, her mind drifting to the darkroom she'd helped Danny set up before the war. He'd been the photographer in the family, patiently teaching her about f-stops and shutter speeds in their small apartment in Lawrenceville. After his death, she'd sold most of his equipment, but kept his Leica hidden away in a drawer, like a time capsule of their shared dreams.

A gravelly voice from the end of the bar cut through her memories. "Moscow anything ain't welcome here," growled Ed Kowalczyk, a former Marine who'd lost three fingers at Guadalcanal. He flexed his remaining digits around his coffee mug, knuckles white with tension. "Bad enough we got Reds in Berlin, now they're trying to get into our drinks."

Marie fixed him with a look that could freeze the Monongahela. "It's just a name, Ed. Like how I bet you still eat German chocolate cake, despite what happened at Bastogne." Her voice carried the same gentle firmness she'd used during the war, when teaching new girls how to handle precision tools without breaking them. She turned back to Martin. "Don't mind him. He's harmless."

Martin handled the copper mug with practiced care, positioning it for the perfect shot. "Actually, we're thinking of rebranding it. Maybe the 'Pittsburgh Mule' - something with local pride. Though your steel workers might take offense to being compared to stubborn beasts of burden."

That got a laugh from the bar, even from Ed. Marie watched intently as Martin demonstrated the camera's features, his movements reminding her of Danny's careful instructions. The morning light caught the developing photograph on the bar between them, the copper mug gleaming like a freshly minted penny against the worn wood.

"Tell you what," she said, an idea forming as she glanced around the bar that had become her sanctuary after the factories let the women go. "You order some food, and I'll show you what this place is really about. I'll even put in an order for 4 cases of vodka, 8 of the ginger beer and pay for the film myself."

Martin straightened in his seat, his expression shifting from polite interest to genuine curiosity. "You know something about photography?"

"Enough to be dangerous," Marie replied, a familiar warmth spreading through her chest as Danny's old tutorials echoed in her mind. "Learned composition from my husband, before Normandy. Learned technical specs reading manuals at Westinghouse during the war. Between the two, I figure I can handle your Polaroid."

Martin settled onto a barstool, ordered a sandwich, and watched as Marie worked the room with the same precision she'd once applied to calibrating aircraft instruments. She caught Big Joe Mazeroski first, his massive forearms scarred from thirty years at the open hearth, holding the copper mug like it was made of the same delicate glass as the photographs he kept of his children. The next shot captured Tommy O'Brien, who'd lost his leg at Anzio but still managed to tend bar three nights a week, mixing a Mule with the same careful attention he'd once given to disarming mines. She even convinced Ed to pose, his remaining fingers wrapped around the mug while he shared stories about coming home - stories he'd never told before the copper mug loosened his tongue.

The photographs materialized slowly on the bar, each one a window into a life shaped by steel and sacrifice. Anna Wojcik appeared first, her callused hands wrapped around the copper mug, still wearing her brother's old work jacket - the same one she'd put on when she'd taken his place at Westinghouse five years ago. The Kovalchuk twins emerged next, fresh off the boat from Ukraine, their faces lighting up at the familiar taste of vodka mixed with something new, something distinctly American.

The twins had arrived just months ago, part of the wave of displaced persons finding new homes in Pittsburgh's neighborhoods. Like many others, they'd found their way to Kelley's, where Marie made sure everyone knew how to pronounce their names properly - a small courtesy they hadn't found many other places in the city.

Martin studied the growing collection of photographs, arranged now like a family album across the bar's scarred surface. He'd been to a dozen bars in Pittsburgh, but none of his own carefully composed shots had captured the city's spirit like these impromptu portraits. "You know," he said, sliding his half-eaten sandwich aside, "I've got a whole marketing department that can't do what you just did in an hour."

The morning light caught the glass-and-steel KDKA radio tower through the window, its red warning lights blinking steadily like a metallurgical heartbeat. The news would be on soon - more reports about Soviet movements, bomb shelters, and the Iron Curtain. But in here, Marie thought, they were just people trying to make their way in a world that had changed too fast, finding comfort in copper mugs and shared stories.

Martin finished his sandwich and pulled out a business card, its crisp edges a stark contrast to the worn bar top. "Smirnoff's looking to expand their advertising department. We need people who understand both the technical and human elements. Someone who can tell a story in a single shot." He gestured at the photos spread across the bar like pages from a family album. "Like these. The pay's good, and there's travel involved. What do you say?"

Marie's fingers traced the embossed letters on the card as her mind drifted to Danny's Leica, still waiting in its drawer after all these years. Maybe it was time to let both the camera and herself step back into the light. "Could be," she said, tucking the card into her apron pocket. "But first, one more shot."

She gathered her regulars together - the morning crowd that had become family since she'd started tending bar after the war. Big Joe moved to the back, his height making him visible above the others like one of the mill's towering smokestacks. Ed stood proud despite his missing fingers, while Tommy O'Brien balanced against the bar, his prosthetic leg hidden by the crowd but his dignity intact. The Kovalchuk twins squeezed in near the front, their copper mugs raised in a toast to their new home. She even convinced Anna to join, still in her work clothes from the night shift, coal dust mixing with hope in the morning light.

"This one's not for advertising," Marie said, adjusting the camera settings with the same care Danny had once shown her. "This one's for us."

As Martin carefully packed away his samples, the lunch crowd began filtering in, bringing with them the familiar symphony of work boots, coffee cups, and conversations that wove together the old world and the new - war stories mixing with baseball scores, just as vodka now mixed with ginger beer in copper mugs that gleamed like the city's ever-burning furnaces. Outside, the snow began to fall again, but inside Kelley's, something new was developing, one story at a time.

The Moscow Mule, a member of the "mule" (or buck) family of cocktails, emerged from a moment of marketing inspiration at Hollywood's Cock 'n' Bull bar in 1940. The story begins with vodka, a spirit that accounted for less than 1% of U.S. spirits consumption at the time, mostly among Eastern European immigrants.

The tale starts with a series of business transactions. The Smirnov family, having fled the Russian Revolution in 1917, had struggled to establish their brand (respelled as "Smirnoff" in French) in Europe. The U.S. rights eventually landed with Rudolph Kunett, a Russian-American immigrant, who in 1938 sold the license to John Martin at Heublein for $14,000 (about $300,000 today). Martin, born to American parents in England and a Cambridge graduate, saw that vodka couldn't compete with gin and decided instead to target the whiskey market.

Martin's connection to Heublein was deep - his mother was the former Alice Heublein, an heir to the company. He and Kunett traveled to California where they met Jack Morgan, owner of the Cock 'n' Bull on the Sunset Strip. Morgan faced his own marketing challenge: he had commissioned a private label ginger beer that wasn't selling because Americans preferred the sweeter ginger ale.

Behind the bar that day was Wes Price, who later offered a practical explanation for the drink's creation: "I just wanted to clean out the basement. I was trying to get rid of a lot of dead stock -- Cock 'n' Bull ginger beer that we made and 100 cases of vodka that we had to buy then in order to get other liquors."

The copper mug, now iconic to the drink, also came from a fortuitous business problem. According to Martin, a "great big, beautiful, buxom woman" named Oseline Schmidt had inherited a copper factory from her father but couldn't find buyers for its products. She was present during the drink's creation, and her mugs became an integral part of the cocktail's identity.

Price tested the new concoction on tough-guy actor Broderick Crawford and adventure-film star Rod Cameron. "It caught on like wildfire," he recalled. However, just as business was taking off, Pearl Harbor was attacked in December 1941. Both Morgan and Martin joined the military, with both men serving with distinction and receiving numerous decorations including the Legion of Merit.

The drink's real explosion in popularity came after the war, around 1946, when Martin launched an innovative marketing campaign using the newly invented Polaroid camera. His technique was brilliant in its simplicity: he would visit bars early in the day, equipped with a Moscow Mule mug, Smirnoff vodka, Cock 'n' Bull ginger beer, and his Polaroid camera. After convincing reluctant bartenders to try the "Russian dynamite," he would snap two Polaroid pictures - one for the bartender to take home and another to show the next bar. This grassroots campaign, combined with press coverage, helped establish the Moscow Mule across America.

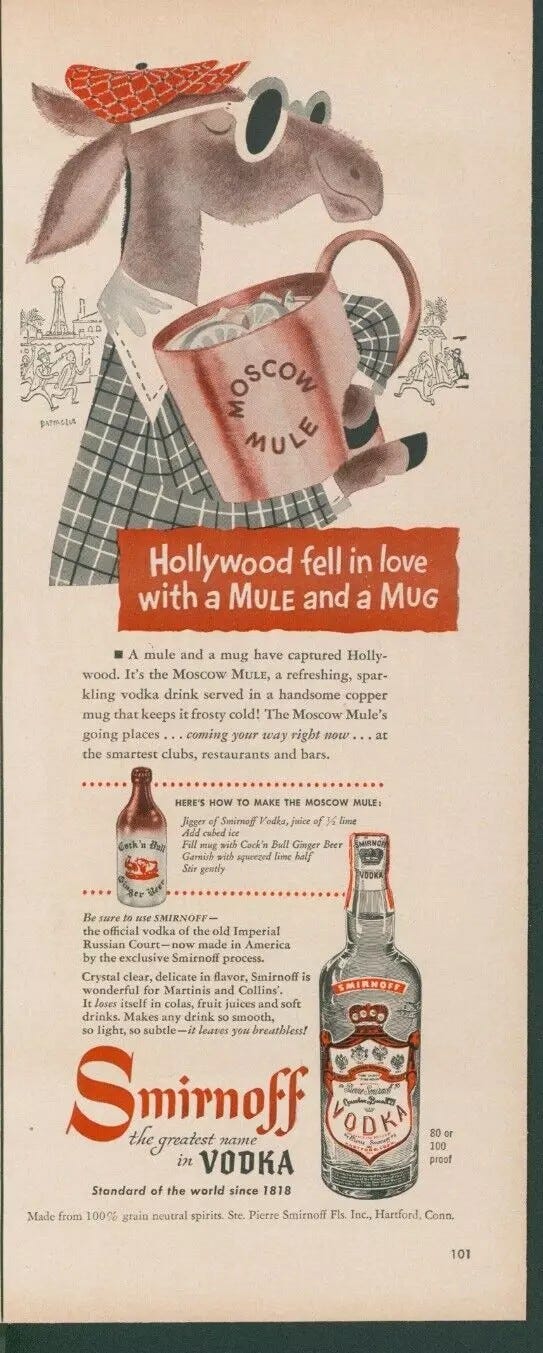

The marketing continued with newspaper ads proclaiming "Hollywood Loves Moscow Mules" and featuring a mule in a suit with the tagline "Tired of the same old drinks?" By 1950, ads declared "Hollywood fell in love with a MULE and a MUG," showing a mule dressed for golf in tartan plaid and sunglasses.

The Moscow Mule's success helped establish vodka as America's most popular spirit, a position it has held for decades. The drink has enjoyed a recent revival, sparked by the classic cocktail renaissance and pop culture appearances, including being featured among the 38 drink recipes in the "Mad Men" cocktail guide and as one of Oprah Winfrey's "Favorite Things for 2012."

This simple combination of vodka, ginger beer, and lime, served in its distinctive copper mug, stands as a testament to American marketing ingenuity and the power of collaboration in solving business challenges. As John Martin noted about the name's origin, while he couldn't recall exactly how they chose it, "I imagine that it had to do with the kick" - a kick that would help transform American drinking culture forever.

The classic recipe remains simple:

- 2 oz vodka

- 4 oz ginger beer

- 1 lime half, squeezed

- Serve over ice in a copper mug

Always enjoy your writing

Have a good winter wherever u r

Les

Hi Michael -- another good one, my favorite drink. When I travel I like to try the Moscow Mule in the hotel bar. Most are only so so. I wish I could remember the name of the hotel where I didn't actually stay, in Georgetown in DC, where I had the best ever. I was staying two doors down. Have you tried a cucumber mule? Had two of those in Bremerton, Washington. On a hot day, for Washington, the first one was so refreshing I had to hold myself back from just downing it. Still loving your stories. Genie