The South Pacific: Sailing to Myself

To paradise and back again

As I worked on getting my sailboat, Saoirse, ready to sail around the world, I dreamed of the adventures that awaited me in Mexico and the South Pacific. Living aboard and preparing for this journey had consumed me for years.

It was during this time of intense preparation that I met Brendan, a master shipwright who had a lifetime of experience working on sailboats. His advice and guidance were invaluable as I navigated the complexities of preparation.

As Brendan and I chatted on the dock one day, swapping stories of our sailing adventures, I found myself hanging on his every word. He told me stories of delivering Transpac boats back from Hawaii to Seattle after the race, painting a vivid picture of life at sea. Brendan had me hooked with his tales of growing up sailing and racing in Southern California.

When Brendan asked if I wanted to crew on a vessel sailing from French Polynesia to Seattle via Hawaii, I didn't hesitate for a second. This was the opportunity I had been dreaming of - a chance to test my skills on a real blue-water passage, a multi-day sailing voyage out on the open ocean. With my own plans to cruise around the world solo, this six-week journey felt like the perfect stepping stone. I leaped at the chance, eager to learn everything I could.

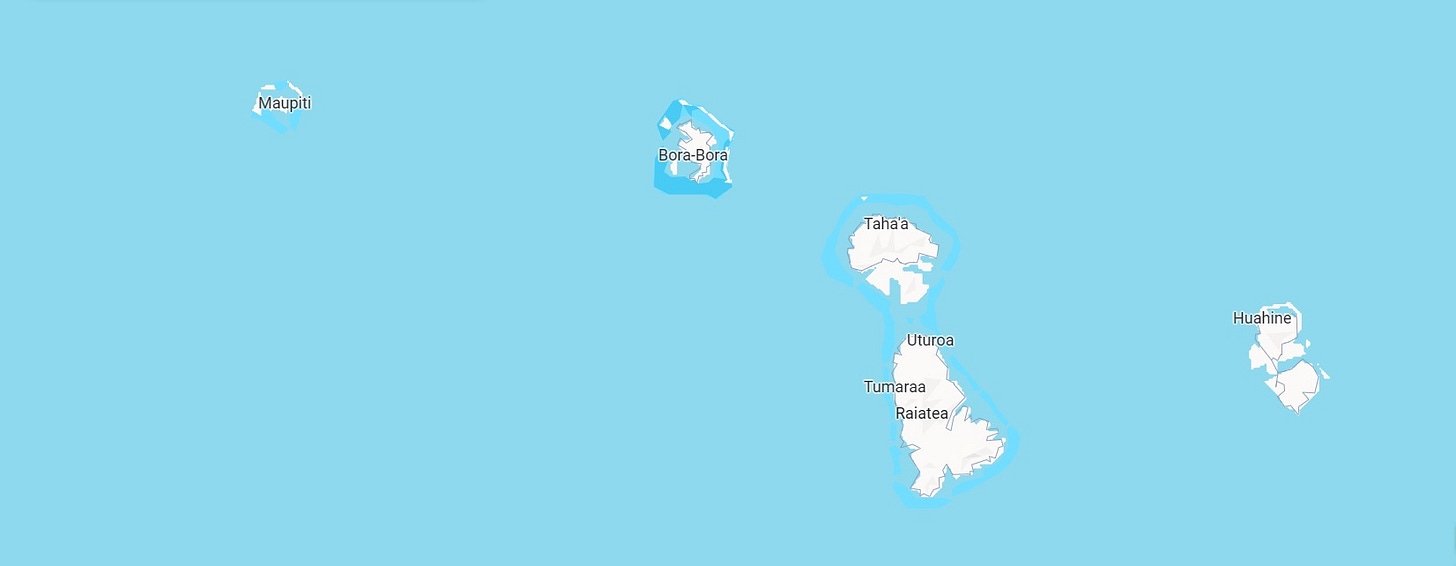

I flew to French Polynesia, arriving in Bora Bora. As the plane touched down, I glimpsed aerial views of the dazzling turquoise lagoon, barrier reef, and Mount Otemanu's craggy silhouette.

The airport is small, partly open air, and sits on a motu, a sand barrier island around the outside of the main island. I picked up my luggage and boarded a small ferry that took me to the main town of Vaitape.

I was struck by the blues of the water. Like Ireland's forty shades of green, there are at least forty shades of blue from a deep blue to a vivid cyan to a clear turquoise. The wind was a constant presence, varying in strength from 10-30 knots, but always warm and refreshing.

Bora Bora, with its towering volcanic core and ring of small islands and reef islets, has been inhabited since ancient times. Today, remnants of a 1940s American Navy base sit alongside the modern town of Vaitape.

I learned that in Tahitian, the island is actually called Pora Pora, meaning "First Born" after Raiatea, the mother island of Polynesia, as the letter "b" doesn't exist in their language.

Bora Bora was all I imagined a tropical island to be, with a towering peak swathed in dense jungle at its heart, surrounded by electric blue waters, swaying palms, and postcard-perfect beaches.

My friend Brendan, the boat's captain, met me at the dock in Vaitape. He was his usual cheerful self in a sun-bleached baseball cap to ward off the tropical sun. He informed me that the boat needed some work before our crossing, and we had just over a week to complete his punch list.

We got into a battered dinghy and headed out to the sailboat to meet Fiona.

Brendan said 'You'll like her, she's Irish. She's living on a wooden sloop on F Dock.'

I am once again amazed at the diversity of people living on their boats in Seattle.

Brendan had found her and she was up for an adventure. Fiona had no blue water experience but knew how to sail and had the right attitude. She had red hair in a pageboy cut with bright shining eyes. She was smart and sarcastic and I was immediately smitten.

We got our jobs done and took the time to enjoy the magnificent lagoon. I spent my days immersed in a kaleidoscopic underwater world, swimming amidst coral gardens in every hue and gliding alongside majestic manta rays. The balmy water was like an endless swimming pool, comfortable enough to stay in for hours.

One evening, as Fiona and I sat on the deck beneath a canopy of stars, she opened up about her dreams. "I've been living on my boat in Seattle for two years now," she confessed, her eyes shining with longing. "But deep down, I've always wanted to push my limits. So when Brendan offered me this chance, I knew I had to jump on it."

One day the cruise ship arrived and disgorged swarms of passengers into sleepy Vaitape, filling the town with a bustle of tour groups. Most never ventured beyond the tourist traps to experience the true slice of paradise that lay just offshore.

We made the mistake of going shopping that day. The hungry horde from the cruise ship had bought up the town's entire day's supply of bread. *Sacre bleu!*

I liked our unhurried pace, interactions with people, and opportunities to embarrass myself with the very little French I remembered from secondary school. However, the smiles, good humor, and patience I was rewarded with made it worthwhile.

The islanders are warm, beautiful people. Paul Gauguin lived here (after working on the Panama Canal) and the beauty of the people is reflected clearly in his paintings. While walking through town to the local shop, I met a group of schoolchildren (7-8 years old) walking along with their teachers, two by two. They filed past with smiles and a cheerful "bonjour" until one little girl put out her hand to shake. Suddenly, I felt like I was part of the royal family. They all wanted to shake hands and give me a big smile, and no one wanted to be left out.

After a memorable few days exploring Bora Bora, it was time to prepare for the next leg of our journey. Early the following week, we planned to sail to Raiatea to stock up on fuel and propane before setting off across the Pacific towards Hawaii.

The boat was Nomad, a 43ft cutter-rigged sailboat. She was ready to go. As we sailed past Bora Bora Yacht Club, I could see a multinational fleet of vessels - French, American, English, and Swiss - and I hoped to see my own Saoirse here too someday.

When we slipped out of the lagoon into the Pacific Ocean, I was struck by the sheer vastness of the water surrounding us. The boat heeled smoothly as the sails filled and we surged forward, the bow slicing through rolling swells.

As we hit a rough patch of weather, Fiona sprang into action, her keen instincts for the wind and waves guiding her as she expertly adjusted the sails. "I love this," she said with a grin, her Irish lilt dancing through her words.

When we arrived at Raiatea, we dropped anchor near the boatyard and took the dinghy to shore, where we were to pick up our last crew member.

Ray stepped onto the sun-drenched dock, his weathered duffel bag a heavy weight over his shoulder. As a retired Navy man in his 60s, Ray's life had been defined by the thrum of powerboat engines and the vast, open sea. Yet, here he found himself a fish out of water, disoriented in this languid paradise.

From the moment his boots touched the wooden planks, Ray's discomfort was palpable. His gaze darted restlessly, taking in the palm trees that swayed with a rhythm he couldn't sync with, to the whispers of turquoise waters caressing the sailboat hulls. It wasn't just the sailboats that unsettled him; it was the tranquility of this place.

Wandering through the vibrant markets of Raiatea in search of last-minute supplies, I couldn't help but be swept up in Fiona's infectious curiosity. She made friends everywhere she went, her quick wit and easy charm bridging any language barriers. Pulling out colorful local bills, she bought a handmade leather pouch. "We can learn so much from other cultures," she mused. "The key is keeping an open heart."

Late that night, Fiona and I found ourselves alone on the deck, the stars sprawling overhead. As we shared stories of our pasts and dreams for the future, I realized how much I had come to trust her and appreciate her outlook. Time slipped away unnoticed until the sun began to paint the sky in hues of orange and pink.

Heading to Hawaii, we would be sailing into the wind, to windward. It is said you sail hard on the wind. It's uncomfortable, the boat pounds into the waves but it is the most direct route.

As we set sail from Raiatea, bound for Hawaii, anticipation and nerves churned inside me, mirroring the restless sea beneath the hull. The ocean itself seemed to beckon, challenging me to confront the unknown. This was to be my first offshore experience; I had never been out in the blue water before.

As the sun began to set that evening, I took my place for my first night watch at sea. To my relief, everything went smoothly. After handing over the watch to Fiona, I lay on the settee, drifting off to the sound of water rushing by the hull. But a couple of hours later, I jolted awake, realizing the noise wasn't coming from outside the boat.

Water gushed inside, sloshing violently from bow to stern, the floorboards bobbing in the chaos. 'Water down below!' I shouted. Brendan burst from the aft cabin, rubbing sleep from his eyes, bare feet splashing through the flood.

Brendan took charge, his calm authority galvanizing us into action.

"Michael, Fiona, shorten sail, we need to dampen down this motion."

"Ray, turn on the bilge pumps."

The wind and seas had been building and we were surfing down eight-foot swells.

As we shortened sail, we drove into the waves, green water washing over the decks. The motion abated slightly.

Brendan picked up the floorboards and stowed them neatly on the sofa. Everything was soaked. He looked over at Ray.

Ray rushed to the electrical panel and flipped the switch for the electric pumps, hoping to clear the water quickly. But after a tense few moments, he realized it wasn't making any difference, the reassuring hum of the pumps never came. Grabbing the manual pump, he started pumping with all his strength.

There's a saying that nobody pumps like a scared man with a pump. It's the truth.

After what felt an hour of frantic pumping, he finally managed to clear the water from the boat. As the last of it drained away, we could see the source of the problem: a jagged crack at the keel stem, gaping open like a wound. As we went to windward, each time we slammed into a wave a surge of water would come into the boat.

We weren't in imminent danger of sinking as the water level wasn't rising rapidly, but everything on the cabin sole, including bags of clothes and unstowed provisions, was completely soaked.

We gathered up the bags of clothes on the floor and tried to separate the wet items from the dry ones. Ray was assigned to monitor the hand pump, his calm presence made it clear we were back in control again.

We managed to pack the crack with towels and random bits of clothes, stemming the flow of water for the moment. But there was no telling how long our makeshift repair would hold.

With the immediate crisis averted, we allowed ourselves a moment to breathe. But as the adrenaline wore off, the gravity of our situation sank in. We gathered in the cockpit, exchanging loaded glances, our great adventure had turned into a nightmare, and now we faced a critical choice: press on with a damaged boat, or turn back to safe harbor.

This was a true "come to Jesus meeting", one of those serious conversations you have to address major problems and make crucial decisions. It's the kind of meeting that's both fascinating and terrifying to be part of, a project management term for that moment when the shit has hit the fan but not everyone has quite grasped the full implications yet.

Brendan broke the heavy silence. 'What should we do?' he asked, his voice grave.

We all looked around at each other - me at Ray, Ray at Fiona, Fiona at Brendan, Brendan at me. Nobody wanted to be the first to speak. I've been in this meeting many times, when everybody knows something is wrong but people are reluctant to admit what needs to be done. I'm always the one to speak up.

In my experience, if something's fucked up, it's always better to face it head-on and fix it rather than deny the problem and let it bite you in the ass down the road.

I broke the silence.

'Let's look at where we are. We're taking on water, the electric pump isn't working. We can't fix this hole at sea, the nearest boatyard ahead is Hawaii, at least 20 days away. But there's a boatyard 100 miles behind us, just a day's sail.'

I took a breath, the weight of my words sinking in. 'I think we should turn back.'

Fiona struggled with the decision. 'I don't want to give up,' she confessed, her voice barely a whisper. 'But we should be safe.'

I looked around and saw everyone nodding in agreement. Just like that, the unspeakable had been said and we all acknowledged this was our plan. We turned around and limped back to Raiatea, riding downwind. With our improvised plug, minimal additional water made its way in.

We surfed down the waves into the pass and across the lagoon. When we arrived at the boatyard, Brendan swiftly organized for the boat to be hauled out so that we could examine the crack. The haul-out was scheduled for the following week; work on the boat would take several weeks, depending on the owner's insurance.

All of this caused a problem for the crew. We had all planned on a two-month trip returning to Seattle by the end of June. The fact that we wouldn't return until the end of July at the earliest caused some serious logistical issues, not to mention our shaken faith in the boat and frustration with the owner for not disclosing such a critical structural problem.

Would we wait for the insurance to fix the boat? Over the next few days, I watched Fiona wrestle with this dilemma. Ray, on the other hand, seemed to be counting down the minutes until he could return to the land of Big Macs and English speakers.

Brendan came to us the next day and laid out the situation.

The insurance company agreed to repair the boat, but the process would be painfully slow. An appraiser would need to fly out just to start the claims process, stretching the timeline out for months.

Ray made no secret of his eagerness to leave what he called this " 'godforsaken speck of sand in the middle of nowhere.' " He paced the dock, muttering under his breath about "I just wanted a goddamn burger" and "never setting foot on a sailboat again."

I couldn't help but chuckle at his frustration. For some people, navigating a foreign language and culture can be overwhelming, making even the simple task of ordering a meal seem insurmountable.

Fiona and I exchanged a long look, a silent understanding passing between us. We had both reached the same conclusion: there was no way we were setting foot on that boat again, not after what we'd just been through. The risk was too high, and the trust too broken.

Brendan broke the news to the boat's owner, who had bailed on the trip at the eleventh hour, leaving us to deal with this whole situation. His voice was tight with frustration as he explained that there was no way we could stick to the original schedule, not with the extensive repairs needed.

The owner booked tickets for us to fly home. I had quit my job and wasn't in any rush, so I set my return flight for two months later. I told Brendan that if the repairs were finished by that time, he could call me and we could talk.

Two weeks had passed since we first limped back into Raiatea's harbor. Each day seemed to stretch out endlessly, the reality of our situation settling over the boatyard like a heavy fog. The boat perched awkwardly on stands, hauled out of the water—a sad sight compared to the gleaming promise of adventure she had once been.

I found myself wandering the narrow streets of Uturoa, the island's main town, enjoying the friendly smiles of the islanders. I was treated to a Polynesian dance demonstration by the local schoolchildren in their vibrant colors and headdresses.

Ray was gone within a week, his parting words a bitter tirade against the sea and all who sail upon her.

As I walked through the standing rows of sailboats one evening, I stumbled upon Fiona, her gaze lost on the distant horizon. As I approached, she turned to me, and I was struck by the tears glistening in her eyes, catching the moonlight.

"This journey has shown me strength I didn't know I had," she said softly. "I've learned so much about myself, about what truly matters in life."

"What are you going to do?" I asked.

"My boyfriend Greg is going to join me on Huahine," she replied, her voice barely rising above the whisper of the waves. "I never imagined I'd find myself in a situation like this."

As another day drew to a close, Brendan and I sat on the dock, watching the sun sink below the horizon in a blaze of orange and pink. We had fallen into a ritual over the past weeks, walking out onto the dock each evening to watch for the elusive green flash.

In the fading light, Brendan turned to me, a pensive look on his face. "You know, out there on the open water," he said, his voice low and steady, "the sea has a way of stripping everything down to its core. It's just you and the ocean—nothing else matters. It forces you to confront what's truly important: integrity, trust, resilience. Those are the qualities that get you through the storms."

His words stayed with me in the months I spent exploring the islands. I had come seeking adventure, but what I found was something deeper, a glimpse into my own resilience and a newfound comfort with the unknown.

In the end, I flew home two months later, leaving Nomad to an uncertain fate, with a story to be told later.

Back in Seattle, as I stepped aboard Saoirse once again, the lessons of that journey stayed with me. I felt a newfound confidence in my ability to handle a crisis and clarity of purpose. I would be ready to leave.

Your colorful and thoughtful descriptions of the adventure are as engrossing as all your writings. How did Liz fare with you off on your own escapade or is this one fabulous fantasy? I enjoyed this writing very much. Genie

Wow M. What an adventure! Next time you are here you must meet our friend George who did an adventure like that